NAWSA Comes to Grand Rapids

Hosting the National American Woman Suffrage Association

After a heated debate at their 1893 convention, National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) delegates voted to hold every other convention outside of Washington, D.C. Taking advantage of this change, Emily Burton Ketcham invited NAWSA to Grand Rapids for its 1899 convention. Her invitation was accepted over those from Cincinnati, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Minneapolis, and New Orleans. Grand Rapids, a mid-sized city in West Michigan, was set to become just the third city to host a NAWSA convention outside of the U.S. capital.

Press Coverage

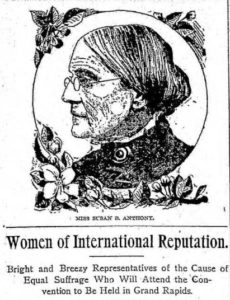

Grand Rapids Herald, April 9, 1899

The convening of so many suffragists in Grand Rapids generated massive media interest. Local newspaper readers were well aware that Susan B. Anthony, Anna Howard Shaw, and other suffragists of international stature would soon convene at their city’s famous St. Cecilia auditorium. Local institutions and businesses put in extra effort to make the suffragists welcome. Bissell CEO Anna Sutherland Bissell even offered delegates factory tours and miniature carpet sweepers engraved with “National American Woman Suffrage Association.”

Women of International Reputation

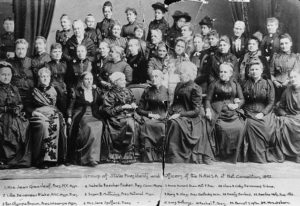

1903, NAWSA leadership, DC Public Library Digital Commons

Grand Rapids had been a hub for suffrage activity before the 1899 convention. In the lead-up to Michigan’s failed 1874 suffrage referendum, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Mary F. Eastman, and Julia Ward Howe had all addressed the city’s suffrage-curious residents. But 1899 was different. Now the movement’s biggest hitters were in the city all at once. Of course, NAWSA president Susan B. Anthony came. But so did future Association presidents Anna Howard Shaw and Carrie Chapman Catt. Other big names included trailblazing Ohio suffragist Harriet Taylor Upton, publisher Henry Blackwell, and journalist Alice Stone Blackwell. With such notable figures, the 1899 NAWSA convention must have captured the attention of the people of Grand Rapids.

The Equal Suffrage Gospel

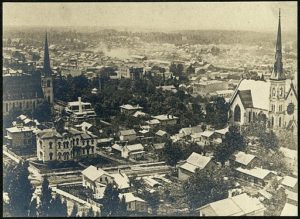

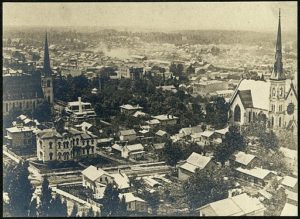

View of Park Congregational (left) and Fountain Street Baptist (right), 1880, Grand Rapids Historical Commission

While many of Grand Rapids’s numerous churches opposed women’s suffrage, some gave NAWSA’s experienced roster of speakers a valuable opportunity to share the equal suffrage gospel. On Sunday, April 30th, they took to pulpits throughout the city. Susan B. Anthony addressed a full house at Fountain Street Baptist Church, Reverend Anna Howard Shaw spoke at Park Congregational, and Laura Clay explored the Bible and its implications for equal rights at Calvary Baptist Church. Several other suffragists preached, including Reverend Antoinette Brown Blackwell, Harriet Taylor Upton, Laura Gregg, Mrs. Colby, Lena Morrow, and Lucy Textor. This church strategy was a wise one for NAWSA; they reached packed audiences and the church settings powerfully countered any perceptions of conflict between the women’s suffrage movement and religious teachings.

Lottie Wilson Jackson’s Resolution

Lottie Wilson Jackson, Berrien County Genealogy

On May 2, the second-to-last day of the National American Woman Suffrage Association’s convention in Grand Rapids, African American suffragist Lottie Wilson Jackson of Bay City, Michigan, asked delegates to address the indignities their black sisters suffered in their travels in support of the suffrage cause by passing the following resolution:

“Resolved, that colored women ought not to be compelled to ride in smoking cars, and that suitable accommodations should be provided for them.”

Her resolution met with passionate opposition. Kentucky suffragist Laura Clay took it as an insult against southern suffragists and dismissed the resolution as irrelevant to the cause and therefore inappropriate. Alice Stone Blackwell came to Jackson’s defense, but it was the opinion of Susan B. Anthony that prevailed in the end. Declaring the issue of separate smoking cars beyond the power of women as the “helpless, disfranchised class” to change, Anthony ended the discussion. The resolution was tabled as “outside the province of the convention.”

Why Grand Rapids?

Emily Burton Ketcham, 1904, Grand Rapids History and Special Collections (GRHSC), Archives, GRPL, GR, Michigan

Why did Grand Rapids serve as the setting for this chapter of suffrage history? The newly built, state-of-the-art St. Cecilia Auditorium was certainly a draw, but the most likely explanation lies in the reputation of Emily Burton Ketcham, Grand Rapids’s premier suffragist. Engaged in the movement as early as 1873, when Michigan suffragists first agitated for a women’s suffrage referendum, she also played a vital part in almost every city suffrage organization in her lifetime. She served four terms as president of the Michigan Equal Suffrage Association, and in 1893 she spoke on women’s suffrage at the Chicago World’s Fair, where she and Susan B. Anthony celebrated the news that Michigan had granted women municipal suffrage rights. Though the law was later struck down, a joint telegram of thanks sent by Ketcham and Anthony to the Michigan governor illustrates her close ties to NAWSA’s leadership.

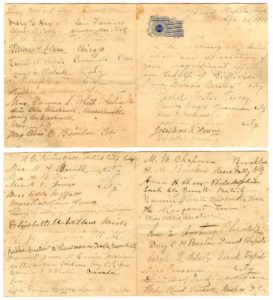

Recognizing Emily Burton Ketcham

1899 NAWSA attendees recognized Ketcham’s long-standing contributions with a card of thanks signed by NAWSA leadership, convention speakers, and local suffragists. This remarkable document contains the signatures of Susan B. Anthony, Anna Howard Shaw, Henry Blackwell and Alice Stone Blackwell. Many city suffragists, including Josephine Goss and Elizabeth Eaglesfield and Lottie Wilson Jackson, also signed the letter.

Bibliography

Anthony, Susan B. and Ida Husted Harper. History of Woman Suffrage. vol. 4. Rochester, NY: Susan B. Anthony, 1902.

Minter, Patricia Hagler. “The Failure of Freedom: Class, Gender, and the Evolution of Segregated Transit Law in the Nineteenth-Century South – Freedom: Personal Liberty and Private Law.” Chicago-Kent Law Review 70, no. 3 (April 1995): 993-1009.

National Association of Colored Women. Minutes of the Second Convention of the National Association of Colored Women. 1899.

NAWSA delegates to Emily Burton Ketcham. April 28, 1899. Ketcham Family Papers. Grand Rapids History and Special Collections Department, Grand Rapids, MI.

Terrell, Mary Church. A Colored Woman in a White World. 1940. Reprint, Toronto: Humanity Books, 2005.

“The Color Resolution.” Woman’s Journal. May 13, 1899.

“The Governor Commended.” Jackson Citizen. May 6, 1893.

“Women of International Reputation.” Grand Rapids Herald. April 9, 1899.

After a heated debate at their 1893 convention, National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) delegates voted to hold every other convention outside of Washington, D.C. Taking advantage of this change, Emily Burton Ketcham invited NAWSA to Grand Rapids for its 1899 convention. Her invitation was accepted over those from Cincinnati, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Minneapolis, and New Orleans. Grand Rapids, a mid-sized city in West Michigan, was set to become just the third city to host a NAWSA convention outside of the U.S. capital.

Press Coverage

Grand Rapids Herald, April 9, 1899

The convening of so many suffragists in Grand Rapids generated massive media interest. Local newspaper readers were well aware that Susan B. Anthony, Anna Howard Shaw, and other suffragists of international stature would soon convene at their city’s famous St. Cecilia auditorium. Local institutions and businesses put in extra effort to make the suffragists welcome. Bissell CEO Anna Sutherland Bissell even offered delegates factory tours and miniature carpet sweepers engraved with “National American Woman Suffrage Association.”

Women of International Reputation

1903, NAWSA leadership, DC Public Library Digital Commons

Grand Rapids had been a hub for suffrage activity before the 1899 convention. In the lead-up to Michigan’s failed 1874 suffrage referendum, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Mary F. Eastman, and Julia Ward Howe had all addressed the city’s suffrage-curious residents. But 1899 was different. Now the movement’s biggest hitters were in the city all at once. Of course, NAWSA president Susan B. Anthony came. But so did future Association presidents Anna Howard Shaw and Carrie Chapman Catt. Other big names included trailblazing Ohio suffragist Harriet Taylor Upton, publisher Henry Blackwell, and journalist Alice Stone Blackwell. With such notable figures, the 1899 NAWSA convention must have captured the attention of the people of Grand Rapids.

The Equal Suffrage Gospel

View of Park Congregational (left) and Fountain Street Baptist (right), 1880, Grand Rapids Historical Commission

While many of Grand Rapids’s numerous churches opposed women’s suffrage, some gave NAWSA’s experienced roster of speakers a valuable opportunity to share the equal suffrage gospel. On Sunday, April 30th, they took to pulpits throughout the city. Susan B. Anthony addressed a full house at Fountain Street Baptist Church, Reverend Anna Howard Shaw spoke at Park Congregational, and Laura Clay explored the Bible and its implications for equal rights at Calvary Baptist Church. Several other suffragists preached, including Reverend Antoinette Brown Blackwell, Harriet Taylor Upton, Laura Gregg, Mrs. Colby, Lena Morrow, and Lucy Textor. This church strategy was a wise one for NAWSA; they reached packed audiences and the church settings powerfully countered any perceptions of conflict between the women’s suffrage movement and religious teachings.

Lottie Wilson Jackson’s Resolution

Lottie Wilson Jackson, Berrien County Genealogy

On May 2, the second-to-last day of the National American Woman Suffrage Association’s convention in Grand Rapids, African American suffragist Lottie Wilson Jackson of Bay City, Michigan, asked delegates to address the indignities their black sisters suffered in their travels in support of the suffrage cause by passing the following resolution:

“Resolved, that colored women ought not to be compelled to ride in smoking cars, and that suitable accommodations should be provided for them.”

Her resolution met with passionate opposition. Kentucky suffragist Laura Clay took it as an insult against southern suffragists and dismissed the resolution as irrelevant to the cause and therefore inappropriate. Alice Stone Blackwell came to Jackson’s defense, but it was the opinion of Susan B. Anthony that prevailed in the end. Declaring the issue of separate smoking cars beyond the power of women as the “helpless, disfranchised class” to change, Anthony ended the discussion. The resolution was tabled as “outside the province of the convention.”

Why Grand Rapids?

Emily Burton Ketcham, 1904, Grand Rapids History and Special Collections (GRHSC), Archives, GRPL, GR, Michigan

Why did Grand Rapids serve as the setting for this chapter of suffrage history? The newly built, state-of-the-art St. Cecilia Auditorium was certainly a draw, but the most likely explanation lies in the reputation of Emily Burton Ketcham, Grand Rapids’s premier suffragist. Engaged in the movement as early as 1873, when Michigan suffragists first agitated for a women’s suffrage referendum, she also played a vital part in almost every city suffrage organization in her lifetime. She served four terms as president of the Michigan Equal Suffrage Association, and in 1893 she spoke on women’s suffrage at the Chicago World’s Fair, where she and Susan B. Anthony celebrated the news that Michigan had granted women municipal suffrage rights. Though the law was later struck down, a joint telegram of thanks sent by Ketcham and Anthony to the Michigan governor illustrates her close ties to NAWSA’s leadership.

Recognizing Emily Burton Ketcham

1899 NAWSA attendees recognized Ketcham’s long-standing contributions with a card of thanks signed by NAWSA leadership, convention speakers, and local suffragists. This remarkable document contains the signatures of Susan B. Anthony, Anna Howard Shaw, Henry Blackwell and Alice Stone Blackwell. Many city suffragists, including Josephine Goss and Elizabeth Eaglesfield and Lottie Wilson Jackson, also signed the letter.

Bibliography

Anthony, Susan B. and Ida Husted Harper. History of Woman Suffrage. vol. 4. Rochester, NY: Susan B. Anthony, 1902.

Minter, Patricia Hagler. “The Failure of Freedom: Class, Gender, and the Evolution of Segregated Transit Law in the Nineteenth-Century South – Freedom: Personal Liberty and Private Law.” Chicago-Kent Law Review 70, no. 3 (April 1995): 993-1009.

National Association of Colored Women. Minutes of the Second Convention of the National Association of Colored Women. 1899.

NAWSA delegates to Emily Burton Ketcham. April 28, 1899. Ketcham Family Papers. Grand Rapids History and Special Collections Department, Grand Rapids, MI.

Terrell, Mary Church. A Colored Woman in a White World. 1940. Reprint, Toronto: Humanity Books, 2005.

“The Color Resolution.” Woman’s Journal. May 13, 1899.

“The Governor Commended.” Jackson Citizen. May 6, 1893.

“Women of International Reputation.” Grand Rapids Herald. April 9, 1899.